Does the Chicano Movement Still Exist?

Does

the Chicano Movement Still Exist?

My

research work aimed to outline the development of historical and cultural construction

and, therefore, to understand how the Chicano identity has progressively been

defined. Through an initially historical-geographical analysis, I tried to

reconstruct the events from which the dense network of relationships that still

binds Mexico to the United States of America was formed. In particular, I was

interested in understanding how this continues to survive within US society,

despite the numerous forces that, over the years, have tried to erase it,

mainly through its assimilation into the dominant culture.

It

is within this framework that this unprecedented cultural construction

originated. For the Chicano, it was a matter of giving voice to a multiplicity

of political, cultural, historical, and national instances, from which a hybrid

and multiple identities were then formed, the result of the encounter-clash

with the previous ones. Chicano is, in fact, a mestizo thought, which is not

simply the product of the fusion, osmosis, or synthesis of several components.

Instead, it is a question of an evolving thought, which arises from comparing

the other. In this confrontation - it is worth reiterating - each of the

parties involved maintains their integrity.

We

have seen the Chicano identity emerge within a liminal space, perfectly

represented by the notion of the frontier. This was preferred within Chicano

Studies - Border Studies to the border one, as it reveals a certain degree of

interaction between the individuals who inhabit it. Within this space, which

lies in between, we do not find two or more monolithic groups that oppose each

other. On the contrary, we are faced with highly heterogeneous groups who find

their richness precisely in this variety of them.

Between the interstices of these two worlds, a sort of cultural nepantlism develops, within which a new figure comes to life, that of the mestizo: a sort of "impure fruit" born from the encounter with the other, representative of hybrid culture and, at the same time, unedited. A culture that was born and developed along with that metaphorical but also physical, cultural, and psychological space that divides Mexico from the United States of America.

As

is evident, the concept of nepantla perfectly explains the condition in which

the Chicano lives. Within this intermediate space, they can reinvent themselves

and create a new image of themselves that incorporates a multiplicity of

meanings. What characterizes them is, in fact, the impossibility of giving up

one of their ethnic components, namely the US or Mexican. Their peculiarity

lies precisely in the fusion and coexistence of both cultures.

The

adoption of these notions, that of the frontier and that of nepantla, has also

allowed the people of La Raza to understand that there are many ways of being

Chicano. This will become particularly evident from the 1970s onwards, when

groups such as the Chicanas, first, and the queer Chicanas, later, detach

themselves from the dominant wing of the movement to give voice to their

identity, not only ethnic but also sexual and gender.

Through

the analysis of the process of Chicano cultural construction, this thesis

proposed - begun in 1848 and continued with an ever greater impulse from the

1960s onwards with the birth and spread of Chicanoism - to cast a glance on the

present. This has made this research anthropology of contemporaneity. I was

interested in understanding this (as reiterated in my introduction to my blog):

Does the Chicano movement still exist? If it exists, in what forms does it

manifest itself today?

Across

the analysis of the data that emerged from the ethnographic work, it was

possible to observe and discover (this is the new aspect or if we want the

integration necessary for my research) how, in reality, Chicanism is not at all

finished, even if it presents itself in forms and modalities different. We are

no longer faced with large demonstrations or long protest marches, and today

the Chicano movement lives substantially in the consciousness and memory of

those who actively took part in it. However, the fact that it survives in the

form of identity awareness does not prevent the Chicanos from continuing to

exert a performative action within US society. In this context, experts have

found it helpful to introduce the notion of agency. This aspect of my

reconstruction work fascinated me a lot because it highlights how we will see

the influence that individuals have on the ability to act in various areas.

Therefore,

the notion of agency allows, together with that of habitus developed by P.

Bourdieu, to better grasp that set of strategies that individuals put into

practice when they are faced with unexpected situations. Habitus is, in fact,

an open system of provisions that continuously generates different practices.

The

concept of "practice" is, in this sense, fundamental to understanding

how these individuals, in our case, the Chicanos, have managed to give life to

a new image of themselves, a new cultural and identity construction that

characterizes and distinguishes them within the dominant society.

Both

notions - of agency and habitus - therefore allow us to show how the capacity

to act of individuals influences their sphere and the broader political and

social sphere and, in turn, they are influenced by it.

Therefore,

we can say that today the Chicano movement lives substantially in the practices

of those who recognize themselves in this specific identity. Through one's work

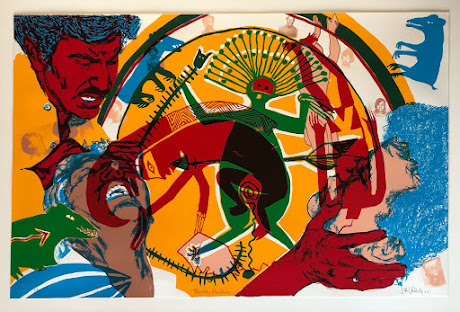

- teaching, art (see the images I proposed at the end of this intervention),

journalism, or literature- keep alive the memory of Chicanism and, with it, its

battles, its victories, and its ideals. In doing so, they aim to preserve all

those values, relationships, and bonds that, together with factors such as that race, ethnicity, and nation, have given rise to what we now call

"Chicano cultural construction."

The

notion of agency can also be applied to individuals of recent immigration, who

- although arriving in the United States with a well-established identity,

history, nationality, and culture - must necessarily intervene actively within

the society host to achieve a certain degree of assimilation and integration.

They are obliged to deal with the new cultures in which they live without

having to be passively assimilated into them and thus lose their identity. They

will always carry the traces of that culture from which they have been molded

since birth. This is why the identity problem hardly arises for new immigrants,

at least in some respects. The Chicanos, on the other hand, experience it as a

deeply felt problem since, for them, it is a question of conquering what, on

the other hand, it is enough to preserve for individuals who have recently

immigrated.

However,

once again, the possibility or not of reinventing themselves depends on the

individual abilities of both, negotiating a new self-image in the immigration context,

capable of rediscovering those certainties that allow each individual to be

truly unique in his plurality and complexity. This is because - quoting

François Laplantine - mestizo thought is "[...] a thought of multiplicity

born of encounter."

Chicano Heaven by John Valadez.

Novelus Kachina By John Valadez.

The Chicano

Identity Told by the Murals in San Diego's Chicano Park.

Located in Barrio Logan, the area is predominantly home to the Mexican-American and Mexican immigrant communities of San Diego. Their struggles integrating into San Diego were furthered by construction work destroying more than 5,000 homes in the area without consultation. Protests through the 1960s, and finally a takeover in 1970, meant that authorities could no longer ignore the community, and Chicano Park was finally completed in 1970.

Historical Mural (Ramp 1A) in Chicano Park portrays the positive contributions of Spanish, Mexican & Mexican-American men in Chicano history. The restoration was completed in 2012 by artists Sal Barajas & Guillermo Aranda. Photo Credit: Robert A. Camacho.

“The Prophecy of Quetzalcoatl”

Depicting Important Symbols in Chicano Culture.

“Love, We Can Do

It,” Our Lady of Guadalupe Mural, by Salvador Barajas.

“Chicano Park Takeover mural shows resistance,

pride, and unity. This mural shows Chicanos and their community gathering to

build their public park. There are men and women of diverse ages taking time

off their hands to create it with success. This Chicano mural epitomizes

Chicanos working for their dreams and the rights that their government wanted

to deny them.”

Comments

Post a Comment